It’s well-known that, as a group, men earn more than women. Despite laws requiring employers to pay men and women equally for equal work, data from the U.S. Census Bureau shows women still earn less on an hourly, weekly, and annual basis overall.

The gender pay gap stems from multiple factors. Partly, it’s due to occupational segregation—men and women being concentrated in different fields. Partly, it’s because of differences in work hours: more women work part-time, while men take on more overtime. And partly, it’s because women take more time off for childcare and other family responsibilities.

Whatever the reasons, the wage gap is problematic. It contributes to poverty among women and families and holds back the entire economy. And since its roots are complex, there’s no simple fix.

Consequences of the Gender Pay Gap

Lower earnings make it harder for women—especially single women—to get ahead financially. It’s tougher for them to save for emergencies or retirement. But the impact isn’t limited to women: it puts families at risk (especially those led by women) and harms the economy as a whole.

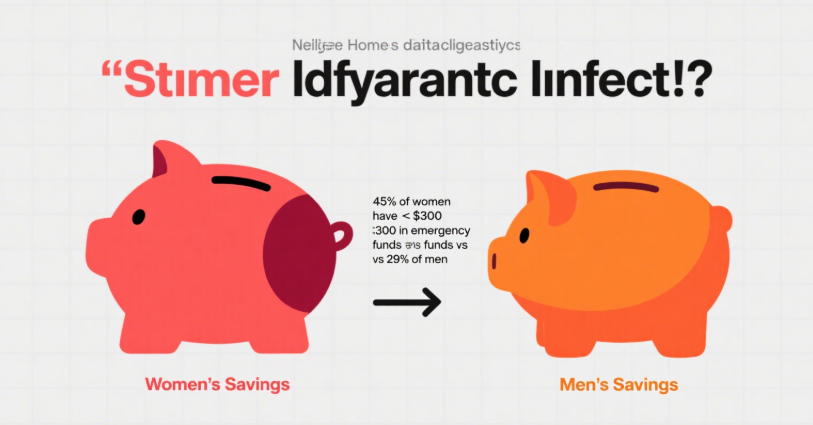

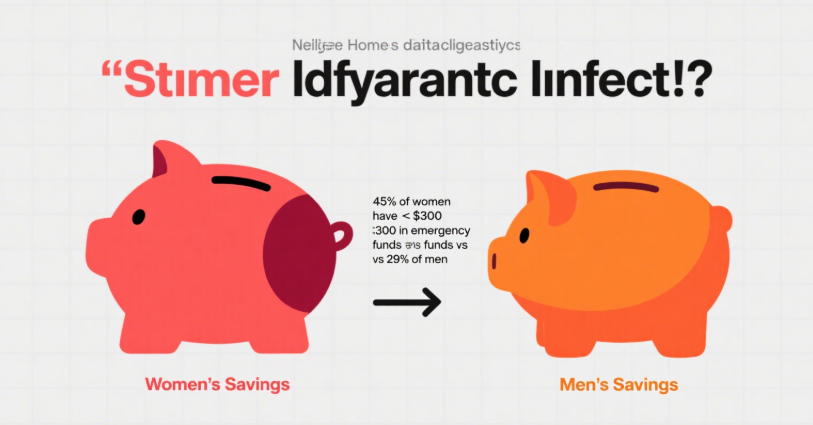

1. The Gender Savings Gap

If men are ahead in earnings, they’re even further ahead in savings. A 2021 GoBankingRates survey found women, on average, have far less in emergency funds than men. Over 45% of women have less than $300 saved, compared to 29% of men. Nearly 25% of men have at least $10,000 set aside, while only 15% of women do.

Pay disparities play a role here. For example, if a woman earns $80,000 a year and saves 9%, while a man earns $100,000 and saves 8%, he’ll end up with about $800 more in savings annually. Over 10 years, that adds up to an $8,000 difference.

Another factor is that women are more likely to take time out of the workforce. A woman might save the same percentage of her salary as male colleagues during her working years, but if she takes five years off to be a stay-at-home parent, her savings drop to zero during that time.

Timing matters too. Thanks to compound interest, saving a little early on yields far more in the long run than saving more later. If a woman takes time off when she’s young—or earns less by working fewer hours during those years—her savings fall behind just when it matters most. By the time she returns to work and ramps up saving, catching up is nearly impossible.

Regardless of the cause, the savings gap leaves many women living paycheck to paycheck. A 2019 MetLife poll (cited by CNBC) found over a third of women say they live this way—roughly five times the rate for men. This makes handling unexpected expenses harder and stymies progress toward long-term goals like buying a home.

2. The Gender Retirement Gap

Women lag even further behind men in retirement savings. A 2019 report from the Transamerica Center for Retirement Studies shows the median household retirement savings for women is just $23,000—less than a third of men’s median amount. Nearly a third of women have less than $10,000 saved for retirement.

Part of the issue is that women are less likely to have access to workplace retirement accounts—partly because more work part-time. About 3 in 10 women say they don’t have a workplace retirement fund, versus roughly 2 in 10 men.

But that’s not the only factor. As noted, women take more time out of work for childcare, losing access to workplace retirement plans during those years. What’s more, even women with such plans contribute a smaller share of their earnings than men. A 2021 T. Rowe Price survey found women of all ages put a lower percentage of their income into 401(k) plans than their male counterparts.

Women have reasons for contributing less: lower earnings leave less room in budgets for savings, and per the Transamerica Center report, they’re more likely to prioritize debt repayment over retirement saving.

This retirement savings gap is doubly unfortunate because women tend to live longer than men—meaning they need to fund more years of retirement with less money. To make matters worse, they also typically receive less in Social Security benefits (which are based on average lifetime earnings). In 2019, women aged 65 and older received an average of $13,505 annually from Social Security, compared to $17,374 for men, per the Social Security Administration.

These factors contribute to poverty among older women. A 2020 Congressional Research Service report shows 8.6% of women aged 65–69 live in poverty, versus around 7% of men. The problem worsens with age: women over 80 are 55% more likely to be impoverished than men in the same age group.

3. Impact on Families

Anything that harms women financially also harms families. A 2020 report from the Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR) shows half of U.S. households with children under 18 rely heavily on a working mother’s earnings—either a single mother or a married mother contributing at least 40% of the family’s income.

Lower-income families depend even more on women’s earnings. Per a 2016 report from the Senate’s Joint Economic Committee, mothers provide an average of 89% of income for families in the bottom 20% of earners.

Women of color are also more likely to be primary family supporters. The IWPR report notes 74% of Black women, 58% of Native American women, and 47% of Hispanic women are primary or major breadwinners for their households.

All this means that when women earn less than men, their families suffer too. Overall household income is lower, and children are more likely to grow up in poverty—putting them at higher risk of poor health, behavioral issues, poor academic performance, and lifelong poverty.

Raising women’s wages would help families in countless ways. Per a fact sheet from the National Partnership for Women & Families (NPWF), closing the gender pay gap would let each working woman afford:

- Over 13 extra months of childcare

- 65 weeks’ worth of family food

- Over 9 months of rent, or over 6 months of mortgage and utility payments

- A full year of tuition and fees at a four-year public university, or full costs at a two-year community college

A 2017 IWPR report calculates that equal pay would cut the poverty rate for working women by over half. The number of children with working mothers living in poverty would fall by nearly half. Close to 26 million U.S. children would fare better if their mothers earned as much as men.

4. Impact on the Economy

Since the 1960s, the number of working women in the U.S. has grown dramatically. A 2017 Brookings Institution report notes only 37% of women were in the labor force in 1962; by 2000, that rose to 61%. This increase is estimated to have boosted the economy by about $2 trillion.

But the economy could benefit even more if women earned as much as men. The IWPR states pay equity would raise the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP) by 2.8%—$512.6 billion—annually.

Higher pay could also draw more women into the workforce, further boosting the economy. A 2017 International Monetary Fund fact sheet shows if women worked for pay at the same rate as men, U.S. GDP would rise by 5%—with even larger increases in other countries.

Long-term, the economic gains from equal pay could be greater: better wages for women mean better conditions for families, so more children would escape poverty. These children would then be more likely to grow into productive workers, whose earnings would strengthen the economy and provide tax revenue to support the growing number of retirees. Eventually, nearly everyone in the country would benefit.

Fixing the Gender Pay Gap

It’s clear fixing the gender pay gap would benefit society broadly—but how to do it is less obvious.

In 1963, the U.S. passed the Equal Pay Act, requiring equal pay for equal work. But over 55 years later, the wage gap still hovers around 20%. Better enforcement might help, but it alone won’t close the gap.

Since the causes of wage inequality are complex, addressing it will require a multi-faceted approach. Here are some potential solutions:

1. Pay Transparency

One simple way to address the gap is for employers to be more open about pay. Currently, many companies keep salaries secret—sometimes even banning employees from discussing them. Salary negotiations are private, and raises depend on managers’ discretion.

This disproportionately harms women. A 2018 paper in Industrial Relations found women are less likely than men to get raises when they ask; per a summary in Harvard Business Review, women get raises 15% of the time when they ask, versus 20% for men.

When employers must disclose pay, they need a reasonable, data-driven basis for salary decisions—they can’t dismiss women’s raise requests due to unconscious bias against “pushy” behavior.

Payscale’s 2020 study on pay transparency found it can eliminate the gender pay gap for identical jobs—especially at the management level. Female directors earn 91% of what male directors do when pay is secret, but equal amounts when it’s transparent.

A 2018 American Association of University Women (AAUW) report outlines steps companies can take for transparency, including:

- Regular pay audits to spot disparities based on gender, race, or ethnicity

- Allowing employees to discuss salaries and banning retaliation

- Ending the practice of setting new hires’ wages based on prior salary (which penalizes those previously underpaid)

The federal Paycheck Fairness Act aims to make some of these steps mandatory: it would bar employers from silencing workers about salaries, retaliating against them, or using salary history to set wages. It would also increase penalties for Equal Pay Act violations and require government studies of pay disparities.

2. More Flexible Work Schedules

Harvard University’s Claudia Goldin found women earn less partly because they work fewer hours—more work part-time, and full-time women are less likely to put in long hours. These shorter hours have an outsize impact: in many fields, those working long hours earn more per hour than part-timers. This pay structure is common in fields where workers handle clients one-on-one and can’t hand them off—like law, where clients expect to work with their specific lawyer. In such cases, two 30-hour lawyers can’t replace one 60-hour lawyer, so the 60-hour lawyer is more than twice as valuable.

In contrast, fields where employees are easily replaceable (like pharmacy, where all pharmacists access the same patient/drug data via computer) have more equal pay. Two 30-hour pharmacists are as valuable as one 60-hour pharmacist.

Goldin argues making more workplaces like pharmacies—rather than law offices—could help. While legislation can’t enforce this, workplaces are evolving: Silicon Valley already emphasizes work-life balance, and Goldin believes this will spread as workers value it more.

More flexibility would help parents—fathers too. Though few families have stay-at-home dads, married fathers now spend more time on childcare than in the past. Flexible hours would let them play a bigger role without fearing income hits.

3. More Child Care Options

In some professions, team-based client handoffs aren’t possible. For women to earn as much as men there, they need to work the same hours and take less time off—which requires better childcare options.

Full-time childcare is costly: Care.com reports that in 2019, infant daycare cost an average of $215 weekly—over $11,000 annually. For school-age kids, families either pay for after-school care or have a parent (usually the mother) take time off.

Affordable preschool and after-school programs would make two-working-parent households easier. The government could help via childcare subsidies for low-income parents, expanding the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit, and funding early education programs like Head Start.

Goldin also suggested changing the school year structure: if schools ran 9am–5pm year-round (matching work hours), mothers wouldn’t need to take as much time off. Though expensive, this could also improve children’s learning.

4. Family-Friendly Policies

Providing affordable childcare is costly, and many taxpayers resist funding it. But the government can pass lower-cost laws to make workplaces more family-friendly, protecting parents who take time off for childcare from being fired or losing too much income.

Examples of such policies include:

- Paid Sick Days: The U.S. is one of few high-income countries without mandatory paid sick leave. Workers who take time off for illness or childcare often lose pay or jobs. Some states (e.g., New York) and cities require it, but no federal law exists—passing one would help parents balance work and care.

- Paid Parental Leave: The U.S. is the only developed country without guaranteed paid maternity leave. The Family and Medical Leave Act requires large employers to grant 12 weeks of unpaid leave for newborn care, but the 2021 FAMILY Act would amend this to guarantee up to 60 days of partial income for “qualified caregiving” (pregnancy, childbirth, newborn care, or caring for a seriously ill family member).

- Preventing Pregnancy Discrimination: The 1978 Pregnancy Discrimination Act bans pregnancy-based discrimination, but nearly 31,000 workers filed pregnancy discrimination charges between 2010–2015 (per NPWF). The Pregnant Workers Fairness Act would require employers to make “reasonable accommodations” (e.g., allowing sitting or water breaks) and ban retaliation for requests.

- Protecting Caregivers: Federal law bars caregiver discrimination, but some states/cities go further (e.g., Vermont and San Francisco guarantee workers the right to request flexible hours; employers must consider requests without punishment).

5. More Male Caregivers

Women typically handle most childcare and elder care. If kids need homework help, someone stays home with a sick child, or Grandma needs a doctor’s ride, it’s usually the mother—so she needs flexible hours, often pushing her into lower-paying jobs.

Having men take on more childcare could reduce this impact. Pew data shows the share of stay-at-home dads rose modestly from 4% (1989) to 7% (2016), but BLS data shows mothers still spend far more time on childcare than fathers.

Equalizing childcare tasks would let women with young kids keep working, avoiding lost earning years early in their careers and keeping lifetime earnings/savings on par with men’s.

Paid paternity leave could encourage dads to step up: a 2019 Mercer survey found 40% of large companies offered it in 2018 (up from 25% in 2015), but BLS data shows only 16% of private-sector workers (men and women) have access.

Paid paternity leave benefits families: studies show dads who take it are less likely to divorce, more likely to share care/housework, and have better relationships with kids. Their children are more likely to get well-baby checkups, vaccinations, and do better in school (per the American Action Forum).

It also benefits companies: a 2016 Boston Consulting Group analysis (cited by Consultancy.uk) found it helps attract talent, retain workers, boost morale/productivity, and enhance brand reputation.

Long-term, more men in childcare could end the “motherhood penalty.” Companies currently penalize women and reward men with kids, assuming mothers will take time off. If more dads take family leave, this assumption will shift.

6. Integrating the Workplace

Changing gender roles in work and home can also narrow the gap. Since part of the gap stems from career choices, more women entering male-dominated fields (and vice versa) would help.

The IWPR notes “gender integration” peaked in the 1980s–1990s—when the wage gap narrowed fastest. Progress slowed after the 1990s, as did gap reduction.

To promote integration, the IWPR suggests better training and career counseling—encouraging women into “men’s work” (e.g., auto repair) and training them to succeed. It also means attracting more men to female-dominated (“pink-collar”) fields like education, childcare, and nursing—some of the fastest-growing fields.

A 2017 New York Times article notes men avoid these jobs due to low status and lower pay than blue-collar work, but they offer better job security and wage growth. Luring men in could involve technical training (especially for non-college graduates) and rebranding jobs as “manly.” As more men enter, the “women’s work” stigma fades.

Integration alone won’t eliminate the gap: AAUW notes women in male-dominated fields (e.g., computer programming) earn more than those in female-dominated fields but still less than male colleagues.

7. Raising the Minimum Wage

Women—especially women of color—are more likely than men to work low-wage jobs. Raising the federal minimum wage would boost women’s earnings, help families relying on mothers’ income, reduce poverty, and narrow racial wage gaps.

The 2021 Raise the Wage Act would gradually raise the minimum wage to $15 hourly over five years (then tie it to inflation) and increase tipped workers’ base wage (stuck at $2.13 since 1991) to $4.95 immediately, then gradually to $15.

Some states already have higher minimum wages than the federal $7.25—states with the highest (e.g., California, New York, D.C.) are among those with the smallest wage gaps (per an AAUW map). Exceptions exist (e.g., Washington state has a $13.69 minimum but a larger-than-average gap), so raising the minimum wage helps but isn’t enough.

8. Stronger Labor Unions

A 2018 IWPR report found unionized women earn roughly $219 more weekly (30% more) than nonunion women—with bigger gains for women of color. Hispanic women (lowest earners overall) gain $264 weekly (47% more) from union membership.

Unionized women also have better access to benefits: 77% get employer-provided health insurance, versus 51% of nonunion women.

The IWPR argues the government could boost women’s earnings by protecting workers’ right to unionize. Over half of U.S. states have “right to work” laws banning union-only hiring; changing these would strengthen unions and help women access better-paying union jobs.

Home

detail

The Gender Pay Gap: Adverse Impacts of Inequity and Strategies to Rectify Wage Disparities

2025-08-27T14:44:10

It’s well-known that, as a group, men earn more than women. Despite laws requiring employers to pay men and women equally for equal work, data from the U.S. Census Bureau shows women still earn less on an hourly, weekly, and annual basis overall.

The gender pay gap stems from multiple factors. Partly, it’s due to occupational segregation—men and women being concentrated in different fields. Partly, it’s because of differences in work hours: more women work part-time, while men take on more overtime. And partly, it’s because women take more time off for childcare and other family responsibilities.

Whatever the reasons, the wage gap is problematic. It contributes to poverty among women and families and holds back the entire economy. And since its roots are complex, there’s no simple fix.

Consequences of the Gender Pay Gap

Lower earnings make it harder for women—especially single women—to get ahead financially. It’s tougher for them to save for emergencies or retirement. But the impact isn’t limited to women: it puts families at risk (especially those led by women) and harms the economy as a whole.

1. The Gender Savings Gap

If men are ahead in earnings, they’re even further ahead in savings. A 2021 GoBankingRates survey found women, on average, have far less in emergency funds than men. Over 45% of women have less than $300 saved, compared to 29% of men. Nearly 25% of men have at least $10,000 set aside, while only 15% of women do.

Pay disparities play a role here. For example, if a woman earns $80,000 a year and saves 9%, while a man earns $100,000 and saves 8%, he’ll end up with about $800 more in savings annually. Over 10 years, that adds up to an $8,000 difference.

Another factor is that women are more likely to take time out of the workforce. A woman might save the same percentage of her salary as male colleagues during her working years, but if she takes five years off to be a stay-at-home parent, her savings drop to zero during that time.

Timing matters too. Thanks to compound interest, saving a little early on yields far more in the long run than saving more later. If a woman takes time off when she’s young—or earns less by working fewer hours during those years—her savings fall behind just when it matters most. By the time she returns to work and ramps up saving, catching up is nearly impossible.

Regardless of the cause, the savings gap leaves many women living paycheck to paycheck. A 2019 MetLife poll (cited by CNBC) found over a third of women say they live this way—roughly five times the rate for men. This makes handling unexpected expenses harder and stymies progress toward long-term goals like buying a home.

2. The Gender Retirement Gap

Women lag even further behind men in retirement savings. A 2019 report from the Transamerica Center for Retirement Studies shows the median household retirement savings for women is just $23,000—less than a third of men’s median amount. Nearly a third of women have less than $10,000 saved for retirement.

Part of the issue is that women are less likely to have access to workplace retirement accounts—partly because more work part-time. About 3 in 10 women say they don’t have a workplace retirement fund, versus roughly 2 in 10 men.

But that’s not the only factor. As noted, women take more time out of work for childcare, losing access to workplace retirement plans during those years. What’s more, even women with such plans contribute a smaller share of their earnings than men. A 2021 T. Rowe Price survey found women of all ages put a lower percentage of their income into 401(k) plans than their male counterparts.

Women have reasons for contributing less: lower earnings leave less room in budgets for savings, and per the Transamerica Center report, they’re more likely to prioritize debt repayment over retirement saving.

This retirement savings gap is doubly unfortunate because women tend to live longer than men—meaning they need to fund more years of retirement with less money. To make matters worse, they also typically receive less in Social Security benefits (which are based on average lifetime earnings). In 2019, women aged 65 and older received an average of $13,505 annually from Social Security, compared to $17,374 for men, per the Social Security Administration.

These factors contribute to poverty among older women. A 2020 Congressional Research Service report shows 8.6% of women aged 65–69 live in poverty, versus around 7% of men. The problem worsens with age: women over 80 are 55% more likely to be impoverished than men in the same age group.

3. Impact on Families

Anything that harms women financially also harms families. A 2020 report from the Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR) shows half of U.S. households with children under 18 rely heavily on a working mother’s earnings—either a single mother or a married mother contributing at least 40% of the family’s income.

Lower-income families depend even more on women’s earnings. Per a 2016 report from the Senate’s Joint Economic Committee, mothers provide an average of 89% of income for families in the bottom 20% of earners.

Women of color are also more likely to be primary family supporters. The IWPR report notes 74% of Black women, 58% of Native American women, and 47% of Hispanic women are primary or major breadwinners for their households.

All this means that when women earn less than men, their families suffer too. Overall household income is lower, and children are more likely to grow up in poverty—putting them at higher risk of poor health, behavioral issues, poor academic performance, and lifelong poverty.

Raising women’s wages would help families in countless ways. Per a fact sheet from the National Partnership for Women & Families (NPWF), closing the gender pay gap would let each working woman afford:

- Over 13 extra months of childcare

- 65 weeks’ worth of family food

- Over 9 months of rent, or over 6 months of mortgage and utility payments

- A full year of tuition and fees at a four-year public university, or full costs at a two-year community college

A 2017 IWPR report calculates that equal pay would cut the poverty rate for working women by over half. The number of children with working mothers living in poverty would fall by nearly half. Close to 26 million U.S. children would fare better if their mothers earned as much as men.

4. Impact on the Economy

Since the 1960s, the number of working women in the U.S. has grown dramatically. A 2017 Brookings Institution report notes only 37% of women were in the labor force in 1962; by 2000, that rose to 61%. This increase is estimated to have boosted the economy by about $2 trillion.

But the economy could benefit even more if women earned as much as men. The IWPR states pay equity would raise the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP) by 2.8%—$512.6 billion—annually.

Higher pay could also draw more women into the workforce, further boosting the economy. A 2017 International Monetary Fund fact sheet shows if women worked for pay at the same rate as men, U.S. GDP would rise by 5%—with even larger increases in other countries.

Long-term, the economic gains from equal pay could be greater: better wages for women mean better conditions for families, so more children would escape poverty. These children would then be more likely to grow into productive workers, whose earnings would strengthen the economy and provide tax revenue to support the growing number of retirees. Eventually, nearly everyone in the country would benefit.

Fixing the Gender Pay Gap

It’s clear fixing the gender pay gap would benefit society broadly—but how to do it is less obvious.

In 1963, the U.S. passed the Equal Pay Act, requiring equal pay for equal work. But over 55 years later, the wage gap still hovers around 20%. Better enforcement might help, but it alone won’t close the gap.

Since the causes of wage inequality are complex, addressing it will require a multi-faceted approach. Here are some potential solutions:

1. Pay Transparency

One simple way to address the gap is for employers to be more open about pay. Currently, many companies keep salaries secret—sometimes even banning employees from discussing them. Salary negotiations are private, and raises depend on managers’ discretion.

This disproportionately harms women. A 2018 paper in Industrial Relations found women are less likely than men to get raises when they ask; per a summary in Harvard Business Review, women get raises 15% of the time when they ask, versus 20% for men.

When employers must disclose pay, they need a reasonable, data-driven basis for salary decisions—they can’t dismiss women’s raise requests due to unconscious bias against “pushy” behavior.

Payscale’s 2020 study on pay transparency found it can eliminate the gender pay gap for identical jobs—especially at the management level. Female directors earn 91% of what male directors do when pay is secret, but equal amounts when it’s transparent.

A 2018 American Association of University Women (AAUW) report outlines steps companies can take for transparency, including:

- Regular pay audits to spot disparities based on gender, race, or ethnicity

- Allowing employees to discuss salaries and banning retaliation

- Ending the practice of setting new hires’ wages based on prior salary (which penalizes those previously underpaid)

The federal Paycheck Fairness Act aims to make some of these steps mandatory: it would bar employers from silencing workers about salaries, retaliating against them, or using salary history to set wages. It would also increase penalties for Equal Pay Act violations and require government studies of pay disparities.

2. More Flexible Work Schedules

Harvard University’s Claudia Goldin found women earn less partly because they work fewer hours—more work part-time, and full-time women are less likely to put in long hours. These shorter hours have an outsize impact: in many fields, those working long hours earn more per hour than part-timers. This pay structure is common in fields where workers handle clients one-on-one and can’t hand them off—like law, where clients expect to work with their specific lawyer. In such cases, two 30-hour lawyers can’t replace one 60-hour lawyer, so the 60-hour lawyer is more than twice as valuable.

In contrast, fields where employees are easily replaceable (like pharmacy, where all pharmacists access the same patient/drug data via computer) have more equal pay. Two 30-hour pharmacists are as valuable as one 60-hour pharmacist.

Goldin argues making more workplaces like pharmacies—rather than law offices—could help. While legislation can’t enforce this, workplaces are evolving: Silicon Valley already emphasizes work-life balance, and Goldin believes this will spread as workers value it more.

More flexibility would help parents—fathers too. Though few families have stay-at-home dads, married fathers now spend more time on childcare than in the past. Flexible hours would let them play a bigger role without fearing income hits.

3. More Child Care Options

In some professions, team-based client handoffs aren’t possible. For women to earn as much as men there, they need to work the same hours and take less time off—which requires better childcare options.

Full-time childcare is costly: Care.com reports that in 2019, infant daycare cost an average of $215 weekly—over $11,000 annually. For school-age kids, families either pay for after-school care or have a parent (usually the mother) take time off.

Affordable preschool and after-school programs would make two-working-parent households easier. The government could help via childcare subsidies for low-income parents, expanding the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit, and funding early education programs like Head Start.

Goldin also suggested changing the school year structure: if schools ran 9am–5pm year-round (matching work hours), mothers wouldn’t need to take as much time off. Though expensive, this could also improve children’s learning.

4. Family-Friendly Policies

Providing affordable childcare is costly, and many taxpayers resist funding it. But the government can pass lower-cost laws to make workplaces more family-friendly, protecting parents who take time off for childcare from being fired or losing too much income.

Examples of such policies include:

- Paid Sick Days: The U.S. is one of few high-income countries without mandatory paid sick leave. Workers who take time off for illness or childcare often lose pay or jobs. Some states (e.g., New York) and cities require it, but no federal law exists—passing one would help parents balance work and care.

- Paid Parental Leave: The U.S. is the only developed country without guaranteed paid maternity leave. The Family and Medical Leave Act requires large employers to grant 12 weeks of unpaid leave for newborn care, but the 2021 FAMILY Act would amend this to guarantee up to 60 days of partial income for “qualified caregiving” (pregnancy, childbirth, newborn care, or caring for a seriously ill family member).

- Preventing Pregnancy Discrimination: The 1978 Pregnancy Discrimination Act bans pregnancy-based discrimination, but nearly 31,000 workers filed pregnancy discrimination charges between 2010–2015 (per NPWF). The Pregnant Workers Fairness Act would require employers to make “reasonable accommodations” (e.g., allowing sitting or water breaks) and ban retaliation for requests.

- Protecting Caregivers: Federal law bars caregiver discrimination, but some states/cities go further (e.g., Vermont and San Francisco guarantee workers the right to request flexible hours; employers must consider requests without punishment).

5. More Male Caregivers

Women typically handle most childcare and elder care. If kids need homework help, someone stays home with a sick child, or Grandma needs a doctor’s ride, it’s usually the mother—so she needs flexible hours, often pushing her into lower-paying jobs.

Having men take on more childcare could reduce this impact. Pew data shows the share of stay-at-home dads rose modestly from 4% (1989) to 7% (2016), but BLS data shows mothers still spend far more time on childcare than fathers.

Equalizing childcare tasks would let women with young kids keep working, avoiding lost earning years early in their careers and keeping lifetime earnings/savings on par with men’s.

Paid paternity leave could encourage dads to step up: a 2019 Mercer survey found 40% of large companies offered it in 2018 (up from 25% in 2015), but BLS data shows only 16% of private-sector workers (men and women) have access.

Paid paternity leave benefits families: studies show dads who take it are less likely to divorce, more likely to share care/housework, and have better relationships with kids. Their children are more likely to get well-baby checkups, vaccinations, and do better in school (per the American Action Forum).

It also benefits companies: a 2016 Boston Consulting Group analysis (cited by Consultancy.uk) found it helps attract talent, retain workers, boost morale/productivity, and enhance brand reputation.

Long-term, more men in childcare could end the “motherhood penalty.” Companies currently penalize women and reward men with kids, assuming mothers will take time off. If more dads take family leave, this assumption will shift.

6. Integrating the Workplace

Changing gender roles in work and home can also narrow the gap. Since part of the gap stems from career choices, more women entering male-dominated fields (and vice versa) would help.

The IWPR notes “gender integration” peaked in the 1980s–1990s—when the wage gap narrowed fastest. Progress slowed after the 1990s, as did gap reduction.

To promote integration, the IWPR suggests better training and career counseling—encouraging women into “men’s work” (e.g., auto repair) and training them to succeed. It also means attracting more men to female-dominated (“pink-collar”) fields like education, childcare, and nursing—some of the fastest-growing fields.

A 2017 New York Times article notes men avoid these jobs due to low status and lower pay than blue-collar work, but they offer better job security and wage growth. Luring men in could involve technical training (especially for non-college graduates) and rebranding jobs as “manly.” As more men enter, the “women’s work” stigma fades.

Integration alone won’t eliminate the gap: AAUW notes women in male-dominated fields (e.g., computer programming) earn more than those in female-dominated fields but still less than male colleagues.

7. Raising the Minimum Wage

Women—especially women of color—are more likely than men to work low-wage jobs. Raising the federal minimum wage would boost women’s earnings, help families relying on mothers’ income, reduce poverty, and narrow racial wage gaps.

The 2021 Raise the Wage Act would gradually raise the minimum wage to $15 hourly over five years (then tie it to inflation) and increase tipped workers’ base wage (stuck at $2.13 since 1991) to $4.95 immediately, then gradually to $15.

Some states already have higher minimum wages than the federal $7.25—states with the highest (e.g., California, New York, D.C.) are among those with the smallest wage gaps (per an AAUW map). Exceptions exist (e.g., Washington state has a $13.69 minimum but a larger-than-average gap), so raising the minimum wage helps but isn’t enough.

8. Stronger Labor Unions

A 2018 IWPR report found unionized women earn roughly $219 more weekly (30% more) than nonunion women—with bigger gains for women of color. Hispanic women (lowest earners overall) gain $264 weekly (47% more) from union membership.

Unionized women also have better access to benefits: 77% get employer-provided health insurance, versus 51% of nonunion women.

The IWPR argues the government could boost women’s earnings by protecting workers’ right to unionize. Over half of U.S. states have “right to work” laws banning union-only hiring; changing these would strengthen unions and help women access better-paying union jobs.